In this post we train LightGBM to make probabilistic predictions of a continuous target variable. We cover aspects about the model architecture, model training and evaluation that are specific for probabilistic models: in particular, we explain the reasoning behind the choice of the initial score, custom loss, and objective function. The model will be trained on a large dataset using custom loss and objective functions. To achieve this, we will use LightGBM-Dask on a Kubernetes cluster running in Google Cloud. In the provided Github repository, you can find the code to reproduce all steps: from the creation of the required infrastructure to model training and evaluation.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Model Architecture

- Model training

- Model evaluation

- Practical Aspects of Model Training with Dask

- References

1. Introduction

In many real-world scenarios, we need more than just a single predicted value - we also need to quantify the uncertainty around it. For instance, when predicting a 30-minute trip, we might want to know: "What's the probability that this trip will last between 25 and 35 minutes?" Is it 50%? 80%? 95%? This information is crucial for decision-making.

One powerful way to capture this uncertainty for regression problems is to predict an entire probability distribution $\rho$ rather than a single point. The distribution tells us where we expect the forecasted variable to lie, and how certain we are about this expectation. A narrow distribution indicates high certainty; a wide distribution indicates more uncertainty. In this post, we use LightGBM to predict the parameters that fully describe such a distribution.

Problem Setup: Predicting Trip Travel Times

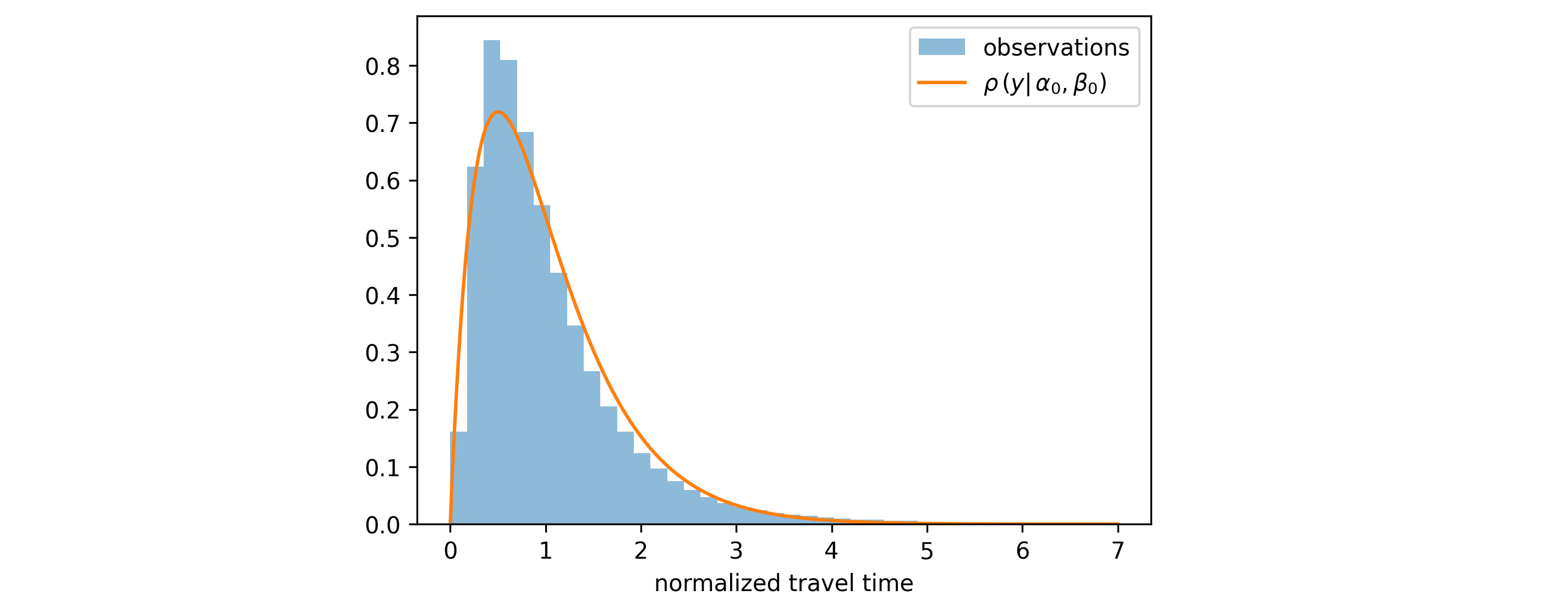

To make the discussion concrete, we focus on the problem of predicting trip travel times. Since travel times should be positive, we choose the Gamma($\alpha$, $\beta$) distribution to model the uncertainty in our predictions. Our task is to predict both distribution parameters $\alpha$ and $\beta$ (that are positive, as well) as functions of the input features $x$: e.g., distance, time of day, weather conditions, etc.

2. Model Architecture: From Inputs to Distribution Parameters

Our model transforms input features $x$ into distribution parameters $\alpha$ and $\beta$ through a two-step process. First, the gradient boosting model produces two raw scores $a_1(x)$ and $a_2(x)$ for each input $x$. These raw scores are then transformed into the positive distribution parameters $\alpha(x)$ and $\beta(x)$ using a mapping function $g$. Below, we examine each step in detail.

2.1 Calculating Raw Scores

For a single input $x$, the gradient boosting algorithm computes raw scores using the standard iterative formula:

\begin{align} \label{eq:eq001} a^{[T]}_j(x) & = a^0_j + \sum^{T}_{t=1} f^{t}_{j}(x) \hspace{10.0mm} (j=1,2) \end{align}The term on the left-hand side is the raw score for output $j$ after $T$ training iterations. The first term on the right-hand side $(a^0_j)$ is the initial score (constant baseline) for output $j$, estimated before any trees are grown. The $f^t_j$ refer to the contribution from the $t$-th tree to output $j$. In our case, $j \in \{1, 2 \}$ because we need two outputs: one will encode the mean value and the other - the rate parameter of the Gamma distribution.

Applying this formula to all $N$ points of the training dataset, gives us $2N$ outputs in total. It's convenient to organize these outputs into a $N \times 2$ matrix $A$, where each row corresponds to one data point, and the first/second column contains all $a_1$, $a_2$ values, respectively. Using matrix notation, the equation becomes:

\begin{align} \label{eq:lgbm_def_matrix} A^{[T]}(x) & = A^{0} + \sum^{T}_{t=1} A^{t}(x) \hspace{10.0mm} A^{t} \in R^{N \times 2} \end{align}The term on the left-hand side refers to the matrix of raw scores after $T$ iterations. The first, second column of the initial score $A^0$, is equal to $a^0_1$ and $a^0_2$, respectively. $A^t$ holds the outputs from the $t$-th pair of trees. Row $i$ $(i=1 \ldots N)$ contains the predictions for the $i$-th data point $x_i$. We'll use this matrix notation when deriving the objective function later.

2.2 Mapping Raw Scores to Distribution Parameters

The raw scores $a_1(x)$ and $a_2(x)$ can be any real numbers (positive or negative). However, the Gamma distribution parameters $\alpha$ and $\beta$ must be strictly positive. Therefore, we apply a transformation $g$ that maps real numbers to positive numbers:

\begin{align} \alpha (x) & = {\rm softplus}(a_1 (x)) \cdot {\rm softplus}(a_2(x)) \nonumber \\ \label{eq:g_map} \beta (x) & = {\rm softplus}(a_2(x)) \end{align} where the softplus is defined as: \begin{align*} {\rm softplus}(x) & = \log \left(1 + e^x \right) \end{align*}The ${\rm softplus}$ function is a smooth approximation of the ReLU function that ensures positive outputs while remaining differentiable everywhere which is essential for gradient-based optimization.

The map defined in \eqref{eq:g_map} might seem like an arbitrary choice, but it has important advantages:

- Interpretable decomposition: $ {\rm softplus}(a_1) = \alpha / \beta$ represents the mean of the Gamma distribution, and $ {\rm softplus}(a_2) = \beta$ represents the rate parameter (inversely related to the scale parameter).

- Separation of roles: The first tree $f_1$ learns patterns related to the average travel time, while the second tree $f_2$ learns patterns related to variability. This separation helps the model learn more efficiently.

Alternative mappings are possible: for example, $\alpha = {\rm softplus} (a_1)$, $\beta = {\rm softplus} (a_2)$, but they don't offer the same interpretability and may lead to slower convergence during training.

3. Model training

3.1 Loss Function

To train our model, we need to define what "good predictions" mean mathematically. Instead of comparing the observed values $\{ y_i \}$ with the model point-predictions we have to compare them with predicted distributions. There are several loss-functions (aka. scoring rules) that can quantify how good is a predicted probability distribution compared to an observation. Here, we will use the negative log-likelihood of the Gamma distribution:

\begin{align} \label{eq:loss_fn} L & = \sum^{N}_{i=1} l_i = \sum^{N}_{i=1} - \log\left[ \rho \left(y_i | \alpha(x_i), \beta(x_i) \right) \right] \end{align}where $l_i$ refers to the contribution to the loss from data point $i$. The Gamma distribution evaluated at the observed trip travel time $y_i$ is denoted by $\rho (y_i | \alpha(x_i), \beta(x_i) )$. Note: In practice, you might normalize this loss by dividing by $N$, but we omit this for notational simplicity.

3.2 Estimating Initial Scores

Before growing any trees, we need to establish baseline predictions: the initial scores $a^0_1$ and $a^0_2$. These are feature-independent constants that provide a reasonable starting point for the iterative learning process. To find them we have to do the following steps:

- Step 1: Find the optimal constant distribution parameters $\alpha_0$ and $\beta_0$ that minimize the loss over the entire training dataset: \begin{align} (\alpha_0, \beta_0) & = \underset{\alpha, \beta }{\mathrm{arg \ min}} \sum^{N}_{i=1} - \log\left[ \rho \left(y_i | \alpha, \beta \right) \right] \end{align} This is a simple optimization problem (no features involved) that can be solved using scipy's built-in maximum likelihood estimation for the Gamma distribution.

- Step 2: Convert these optimal parameters back to raw scores using the inverse mapping $g^{-1}$: \begin{align} a^0_1 & = \rm{softplus}^{-1}(\alpha_0 / \beta_0) \nonumber \\ a^0_2 & = \rm{softplus}^{-1}(\beta_0) \end{align} where $\rm{softplus}^{-1}$ is the inverse of the softplus function.

While we use constant initial scores here, you're not restricted to this approach. You could use a simpler model (e.g., linear regression) to predict feature-dependent initial scores, as long as you use the same loss function \eqref{eq:loss_fn} and you compute initial scores for every point in the training/validation dataset before growing trees. This can give your model a head start, especially if simple linear relationships exist in your data.

3.3 Growing Trees: The Objective Function

Now comes the core of gradient boosting: iteratively growing trees to minimize the loss. To grow each tree, LightGBM requires an objective function that computes the gradient of the loss with respect to the raw scores (first-order derivatives), and the diagonal of the Hessian matrix (second-order derivatives). An explanation how the gradients and the Hessian impact the tree growth is provided in the XGBoost tutorial where an example of growing a single tree per iteration was considered, and Taylor expansion of the loss function up to the second order was applied. We would like to take a closer look at the latter step and see how it changes for our problem.

3.4 Taylor Approximation of the loss function

The foundation of gradient boosting is a second-order Taylor expansion of the loss function w.r.t. the raw scores. We recall again the matrix notation for the raw scores used in \eqref{eq:lgbm_def_matrix}. When we grow the $T$-th pair of trees we update the raw scores by adding to them the matrix $A^t$ $(t=T)$ on the right-hand side. If we assume that the values of the new matrix $A^t$ $(t=T)$ are very small then the update of the total loss $L$ should be small, as well, which justifies the application of the second-order Taylor expansion w.r.t. $A^t$ $(t=T)$: \begin{align} \label{eq:loss_taylor} L^{[T]} &= \sum^{N}_{i=1} l^{[T]}_i \\ & \approx \sum^{N}_{i=1} \Bigg( l^{[T-1]}_{i} + \sum^{2}_{j=1} \frac{dl_i}{dA_{ij}} \vast^{}_{A_i=A^{[T-1]}_i} \hspace{-13.0mm} A^{T}_{ij} \hspace{5.0mm} + \frac{1}{2} \sum^{2}_{jj'=1} \frac{d^2l_i}{dA_{ij} dA_{ij'}} \vast^{}_{A_i = A^{[T-1]}_i} \hspace{-13.0mm} A^{T}_{ij} A^{T}_{ij'} \hspace{3.0mm} \Bigg) \nonumber \end{align} There are few key observations:

- Per-sample structure: Each data point $i$ contributes independently to the loss, which is why the subscript on $l$ matches the first subscript on $A$ which refers to the $i$-th row.

- Mixed second derivatives: The last term in the second line of \eqref{eq:loss_taylor} contains mixed derivatives, i.e. terms where $ij \neq ij'$. However, LightGBM only accepts diagonal Hessian terms.

In this example you can see one of the drawbacks of growing more than one tree per iteration: we get mixed second order derivatives. Since we are asked to provide only the diagonal of the Hessian matrix in our objective function this means that we are practically dropping the mixed derivative terms from the Taylor expansion. The model loses important information that can impact the generation process of a new tree. If we were growing only one tree per iteration we would have never observed mixed second order derivatives, and this problem would not have been present. This approximation explains why we prefer some maps $g$ from raw scores $(a_1, a_2)$ to distribution parameters $(\alpha, \beta)$, like the one in \eqref{eq:g_map} to others.

4. Model Evaluation

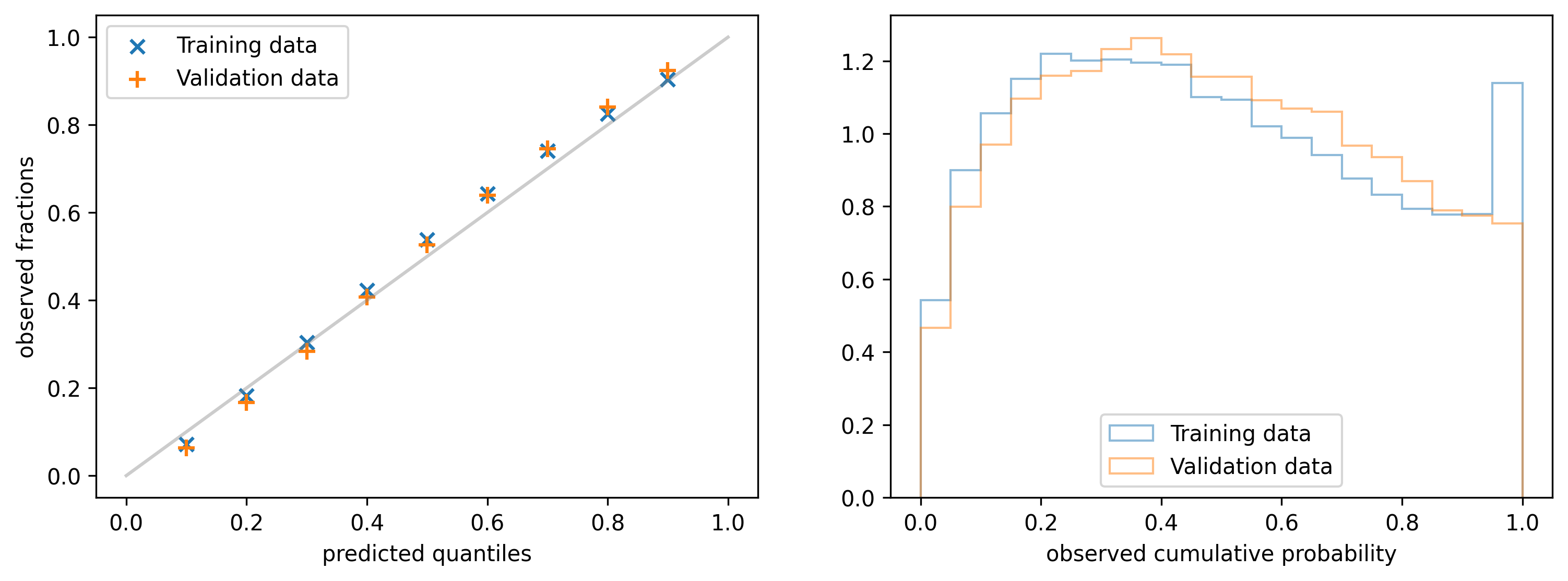

Since we are predicting probability distributions, we would like to know if the model is able to correctly quantify its uncertainty about a prediction. For example, if the observed value lies between the predicted 10-th and 90-th percentile 80% of the times. In addition, we would like to know if the distributions are still sharp enough. To assess both properties we use different plots and metrics.

4.1 Calibration plot

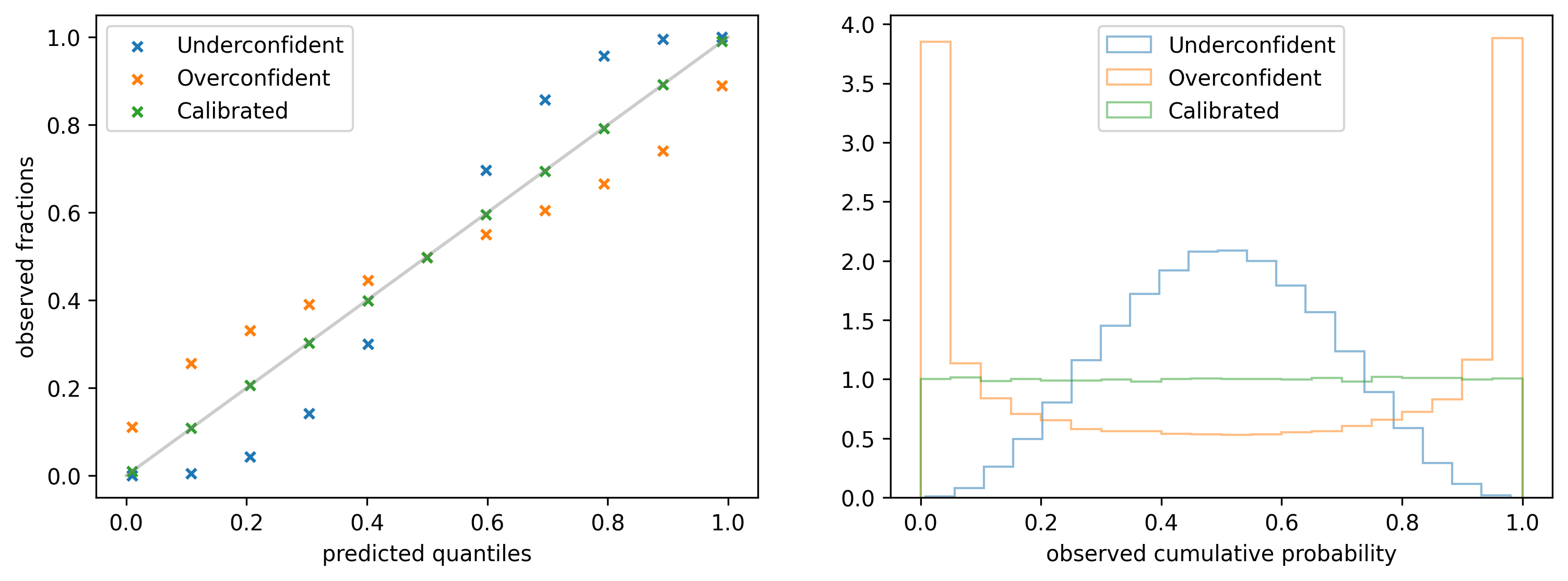

It is obtained by picking a fixed quantile $y_p$ from the predicted distribution for each data point $x$ and calculating the fraction of observations that are below $y_p$ (y-axis). The operation is repeated for a list of quantiles, e.g. $0.1, 0.2, 0.3, \ldots$ (x-axis). If the model is perfectly calibrated the observed fractions should always match the quantiles, as it is shown in the left figure below (green marks).

4.2 Probability integral transform histogram

An alternative representation of the same information is provided by the Probability integral transform (PIT): it is obtained by collecting the quantiles $q_i$ of the predicted distribution $\rho(y| \alpha(x_i), \beta(x_i))$ at which the observed values $y_i$ fall, and building a histogram. The quantiles are obtained with the following equation: \begin{align*} q_i & = \int^{y_i}_{0} \rho(y | \alpha (x_i), \beta(x_i)) dy \equiv CDF(y_i; \rho) \end{align*} where $CDF(y; ρ)$ refers to the cumulative distribution function of $\rho$ evaluated at $y$. On the right side of the figure above you can see the PIT histogram for three different types of models. For a calibrated model (green) the histogram should be uniform in the range $(0, 1)$.

If a model is too uncertain about its predictions then the histogram might have a peak at $1/2$: in the example provided above (blue) 40% of the observations lie within the predicted 0.4 - 0.6 quantile range instead of 20%. To get this number one can either calculate the area btw 0.4 and 0.6 in the histogram or look at the calibration plot and subtract the observed fractions for the same two quantiles. It follows that the predicted quantiles 0.4 and 0.6 are actually 0.3 and 0.7, respectively.

On the other hand, if a model is too certain about its predictions it is likely to observe peaks in the distribution at 0 and 1. In the third example (orange) only 50% of the observations lie in the predicted 0.1 - 0.9 quantile range instead of 80%.

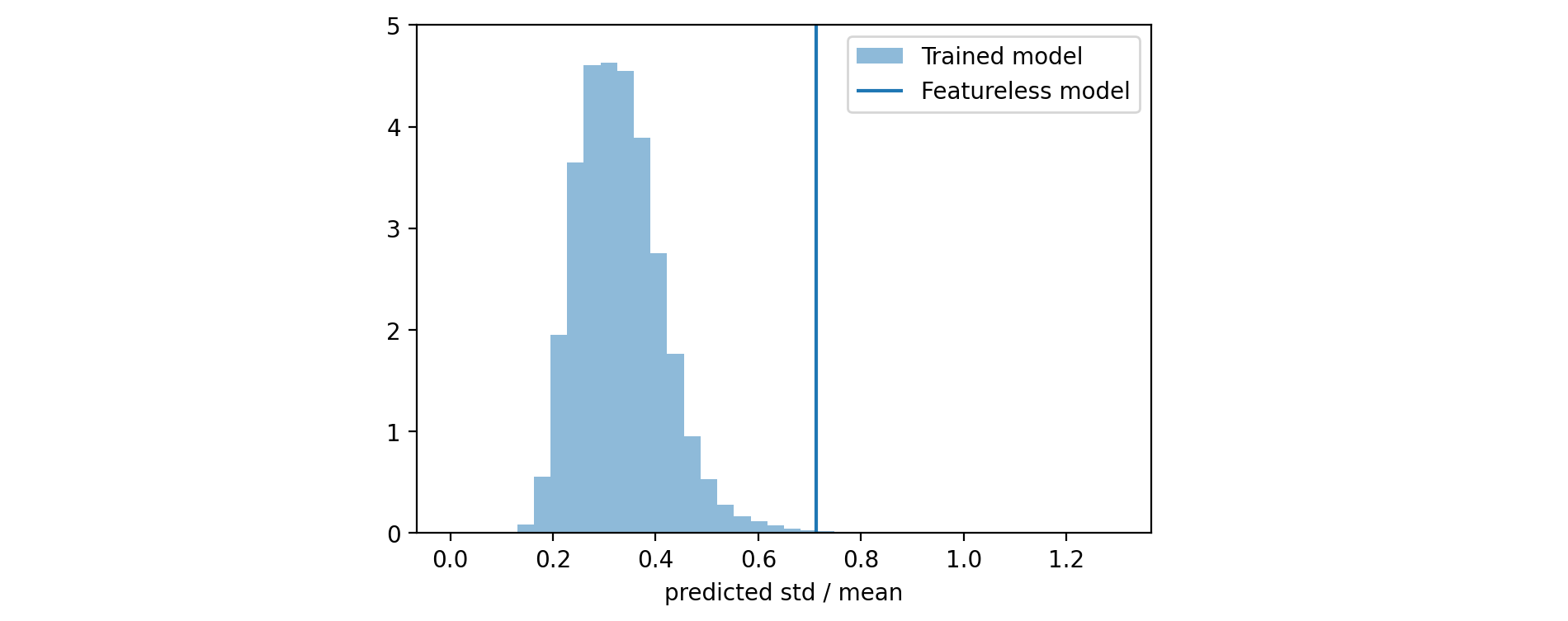

4.3 Relative standard deviation histogram

If you look at the calibration plot of the model that uses only the initial score (generated before starting to train any tree) you will see that it is already calibrated. On the other hand, we expect that this model cannot be very sharp, i.e. it predicts wide distributions with high standard deviation. Our expectation is that the sharpness should improve after each training iteration. To measure it, we can calculate the (relative) standard deviation \begin{align*} \text{rel std} & = \frac{ STD [ \rho ] }{ \mathbb{E} [ \rho ] } = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha(x)} } \end{align*} or the width of a fixed interquartile range of the predicted distribution $\rho(y|\alpha(x_i), \beta(x_i))$ for each $x_i$ and build a histogram from the obtained values.

4.4 Continuous ranked probability score (CRPS)

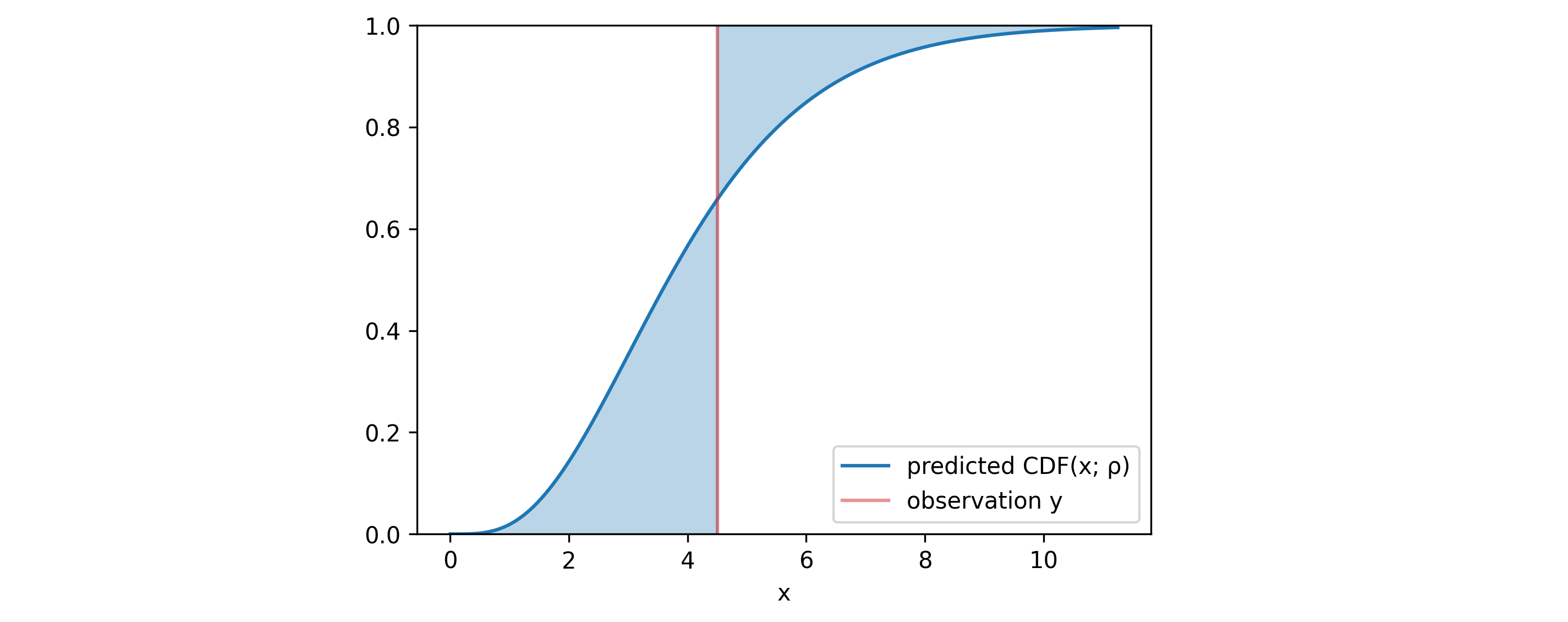

In addition to these plots, one can use a metric that simultaneously evaluates both calibration and sharpness - the CRPS. Given the observation $y$ and the predicted distribution $\rho$, it is defined as: \begin{align} CRPS(\rho, y) & = \int _{\mathbb{R}} \Big( CDF (x; \rho) - H(x-y) \Big)^2 dx \end{align} where $H$ is the Heavyside step function and $CDF(x; \rho)$ is the cumulative distribution function of $\rho$ evaluated at $x$. The blue area in the figure above represents the difference between these two functions. The area, and with it the $CRPS$ would have been minimized if the median of $\rho$ matched with the observation $y$ and if the standard deviation of $\rho$ went to $0$. This limit refers to the case of the model delivering exact point-predictions.

5. Practical Aspects of Model Training with Dask

To demonstrate our probabilistic forecasting approach, we train the model on the NYC Taxi Trip Dataset, a public dataset containing trip records with pick-up and drop-off times, locations, distances, fares, and additional metadata. While data fetching, preprocessing, and feature engineering are straightforward and well-documented in our GitHub repository, this section focuses on why we should use Dask for distributed training and what infrastructure is required to deploy the training pipeline on Google Cloud.

5.1 Why Dask for Distributed LightGBM Training?

The NYC taxi dataset's size necessitates distributed training - training on a single machine is either impossible or prohibitively slow. For distributed gradient boosting, practitioners typically choose between two main ecosystems:

- Apache Spark + SynapseML. It is a mature distributed computing framework with wide adoption but it has the critical limitation of not supporting training a LightGBM model with a custom loss-function, at least not through the PySpark API. An additional challenge is that PySpark generally discourages user-defined functions (UDFs) due to performance overhead from Python-JVM communication. Scala users might be able to overcome these limitations but this is outside of our scope.

- Dask + LightGBM. Dask is an open-source library for parallel computing that is smaller and lighter weight than Spark. It is written in Python and offers a seamless integration with other python libraries like NumPy, pandas, and Scikit-learn. The native LightGBM library supports distributed learning via Dask and since version 4.0.0 it supports custom loss functions, as well.

5.2 Cloud Infrastructure Setup on Google Cloud Platform

We will use Google cloud to create the infrastructure required to train the model:

- A service account to which we will assign different access rights.

- Google cloud storage (GCS) where we will store the training data and the artifacts of the trained model.

- A Kubernetes cluster for the training.

5.3 Dask Deployment on Kubernetes

Once the resources are ready, we can use one of the official Helm charts to set up Dask. The deployment that we will use creates a single Dask scheduler that coordinates the task execution, several Dask workers that execute the computation, and a Jupyter Lab interactive environment for development and experimentation. You can use a jupyter notebook inside Jupiter Lab to execute the data collection, data preprocessing and model training steps. In the end, you have to destroy the Kubernetes cluster since it incurs high costs.

This setup is thought more for experimentation. An automation of the training workflow can be achieved with Vertex AI where the computational resources will be automatically released (destroyed) once the training is done.